“The ability to make good decisions under pressure is a key ingredient to success in any endeavour” - Michael Jordan

In the realm of human experience, few challenges are as formidable as making decisions under extreme pressure or during a crisis. Whether it’s a medical emergency, a natural disaster, a financial meltdown, or a high-stakes military operation, the ability to make sound decisions quickly can mean the difference between success and failure, life and death. The importance of this skill is underscored by the myriad of scenarios where rapid and effective decision-making is not just beneficial but crucial.

The Nature of High-Pressure Situations

This week, at one of our Network Keynote Speaker events, we enjoyed the stimulus provided by our speaker, Stuart, who led combat missions in the Helmand Province of Afghanistan. His insights were invaluable and thought provoking.

High-pressure situations are characterised by urgency, uncertainty, and significant consequences. These conditions create an environment where normal decision-making processes are disrupted. The human brain, under such stress, undergoes physiological and psychological changes that can impact judgement. Stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol surge, which can heighten alertness but also impair cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and logical reasoning.

The chaotic nature of crises often means that information is incomplete, contradictory, or rapidly changing. Decision-makers must navigate these turbulent waters, often without the luxury of time to thoroughly analyse every piece of data. This requires a blend of intuition, experience, and rational thinking to assess the situation, weigh options, and act decisively.

In the storm’s relentless gale, Calm and steady, we set sail. With minds sharp and hearts in sync, Decisions forged, we do not shrink. In chaos, clear paths we find, Strength of heart, and sharp of mind. Pressure moulds, but does not break, Brave choices, our lives remake.

Unattributed

Importance in Various Fields of Leadership

In the medical field, healthcare professionals often encounter life-or-death situations where rapid decision-making is imperative. The ability to quickly assess a patient’s condition, determine the best course of action, and execute that plan can save lives. For instance, emergency room doctors and nurses regularly make split-second decisions about how to treat patients with severe injuries or life-threatening conditions. Their training and experience enable them to prioritise interventions and act swiftly, often under the watchful eyes of anxious family members and colleagues.

Similarly, in the military, commanders must make strategic decisions with limited information, often under intense stress, where the stakes are exceedingly high. The outcomes of these decisions can affect not only the immediate mission but also broader geopolitical dynamics. Military leaders are trained to operate under the concept of “command under pressure,” which emphasises quick, decisive action based on the best available information. Their decisions can impact the lives of soldiers, civilians, and the overall success of military objectives.

In the business world, leaders must navigate crises such as financial downturns, corporate scandals, or market disruptions. The decisions made in these moments can determine the survival and future success of the organisation. Effective crisis management requires not only quick thinking but also the ability to stay calm, communicate clearly, and inspire confidence among stakeholders. For example, during the 2008 financial crisis, leaders of financial institutions had to make rapid decisions to secure liquidity, reassure investors, and comply with evolving regulations. Their actions played crucial roles in stabilising the economy and restoring market confidence.

Creativity is impacted by pressure

Harvard Business School professor Teresa Amabile's research into creativity in the workplace discovered that pressure negatively affects both creativity and productivity. Although some workers felt more creative when under pressure, the fact of the matter is that while they were certainly completing tasks, their performance was actually on a much lower creative level. Pressure affects more than work. The secret to a successful relationship or world class team isn't always chemistry between them, but the ability to interact in pressure moments. For example, couples or teams who criticise each other, saying things like, you're too selfish, you never listen, stop trying to control every situation, put a tremendous amount of pressure on a relationship. As a result, the partnership or team suffers as each individual inevitably feels dissatisfied with the other.

Let’s look at this in more detail and consider the physiological and psychological attributes.

The Psychological Aspect

Psychological resilience, or the ability to mentally and emotionally cope with crises, is another critical factor. This involves cultivating a mindset that can withstand pressure and adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. Techniques such as positive self-talk, visualisation, and focusing on controllable factors can bolster psychological resilience. Moreover, fostering a culture that encourages learning from failures and near-misses can improve collective decision-making capabilities over time.

Positive self-talk can mitigate the impact of negative emotions and maintain focus on the task at hand. Visualisation techniques, often used by athletes and military personnel, involve mentally rehearsing scenarios to prepare for actual performance under pressure. Focusing on controllable factors helps individuals avoid feeling overwhelmed by the broader context and concentrate on immediate actions they can take.

The book “Perform Under Pressure” by Dr Ceri Evans provides a comprehensive guide on how to manage and excel under pressure based on his experience as a forensic psychiatrist and performance coach. Evans explains pressure as a complex interplay of physical, emotional, and cognitive responses triggered by high-stakes situations. He introduces the concept of the “Red Brain” (emotional, reactive) and the “Blue Brain” (rational, analytical). Effective performance under pressure involves managing the Red Brain and engaging the Blue Brain. This dichotomy offers a nuanced perspective on the psychological and physiological responses that influence our performance in high-stakes situations.

Here at Uspire we use the Insights module which use four colours of thinking styles

In a crisis or under extreme pressure Evans argues that our thinking becomes more primitive, and creativity gets suppressed so that we depend on a Red and Blue reaction.

Red Brain: The Reactive, Emotional Brain

The Red Brain represents the more primitive, emotional, and reactive parts of our brain. It includes structures like the amygdala, which is crucial for processing emotions and survival instincts. When we perceive a threat, whether it is physical danger or a psychological stressor, the Red Brain is activated. This activation triggers the fight-or-flight response, releasing stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. These hormones prepare the body to respond to immediate danger by increasing heart rate, sharpening senses, and redirecting blood flow to essential muscles.

In high-pressure situations, the Red Brain’s primary function is to ensure survival. However, in modern contexts, the “threats” we face are often not life-threatening but psychological. These could be job interviews, public speaking, or competitive sports. Despite the difference in the nature of threats, the Red Brain’s reaction remains the same: it prepares us to fight, flee, or freeze.

The issue with the Red Brain’s dominance in non-life-threatening situations is that it can impair our cognitive functions. When the Red Brain takes over, our ability to think rationally, make decisions, and perform complex tasks diminishes. This can lead to panic, anxiety, and suboptimal performance. For example, a golfer might choke under pressure because the Red Brain’s activation disrupts the fine motor skills required for a precise putt.

Blue Brain: The Rational, Analytical Brain

In contrast, the Blue Brain represents the more evolved, rational, and analytical parts of the brain, primarily the prefrontal cortex. The Blue Brain is responsible for executive functions such as decision-making, problem-solving, and impulse control. It allows us to plan, strategise, and execute tasks that require higher-order thinking.

Under normal circumstances, the Blue Brain helps us navigate complex tasks by evaluating information, considering consequences, and making reasoned choices. It is crucial for activities that require careful thought, such as strategic planning in a business meeting or calculating the best move in a chess game.

However, under pressure, the Blue Brain’s functionality can be compromised if the Red Brain becomes too dominant. The key to performing well under pressure is to manage the Red Brain’s responses and engage the Blue Brain effectively.

Balancing the Red and Blue Brain

Dr. Evans emphasises that the goal is not to suppress the Red Brain entirely but to achieve a balance where the Blue Brain can function optimally even when the Red Brain is activated. This balance allows individuals to remain calm, focused, and effective under pressure.

Awareness and Acknowledgment:

The first step is recognising when the Red Brain is taking over. This involves being aware of physical symptoms of stress, such as increased heart rate, sweating, or shallow breathing. Acknowledging these signs can help in addressing them promptly.

Controlled Breathing:

Techniques like deep breathing can help calm the Red Brain. By slowing down the breath, you signal to your body that there is no immediate threat, which helps reduce the intensity of the fight-or-flight response.

Visualisation and Mental Rehearsal:

Engaging the Blue Brain through visualisation techniques can prepare the mind for high-pressure situations. By imagining successful outcomes and rehearsing scenarios mentally, the brain becomes familiar with the process, reducing the Red Brain’s reactivity.

Mindfulness and Grounding Techniques:

Mindfulness practices, such as meditation, can help maintain a state of calm and focus. Grounding techniques, such as focusing on physical sensations or the environment, can help shift attention away from anxiety-inducing thoughts.

Positive Self-Talk:

Replacing negative, fear-based thoughts with positive affirmations can help engage the Blue Brain. Encouraging oneself with phrases like “I am prepared” or “I can handle this” can counteract the Red Brain’s negative bias.

Preparation and Practice:

Thorough preparation reduces uncertainty, which is a major trigger for the Red Brain. Repeated practice builds confidence and muscle memory, making it easier to perform tasks under pressure with less conscious effort.

Reflection and Learning:

After high-pressure situations, reflecting on what went well and what could be improved helps in adjusting strategies for future scenarios. This continuous learning process strengthens the Blue Brain’s capacity to handle pressure effectively.

In the book by Hendrie Weisinger & J.P. Pawliw-Fry, Performing Under Pressure, he develops a system that he refers to as the COTE of armour to deal with pressurised situations.

C onfidence

O ptimism

T enacity

E nthusiasm

Confidence is key to keep you pressing ahead when the going gets tough. As your self-confidence increases, your anxiety reduces, and it becomes easier to perform well under pressure. In fact, several studies have demonstrated that people with higher confidence perform better, work harder, persist longer, and even consider themselves smarter and more attractive than their peers. It's easy to increase your own confidence simply by physically opening your body, lifting your arms up, standing straight, and pulling your shoulders back.

This confidence-building posture often used by performers before going on stage is enough to lower your stress hormones and boost your testosterone, giving you more courage. Like confidence, optimism will help you move forward despite pressure. If you look at things positively and have good expectations for the future, you'll be more likely to do things that can feel uncomfortable or challenging, like taking risks or working hard.

Try starting a pressurised situation by appreciating the good things around you exhibit gratitude.

Tenacity and enthusiasm complete your “COTE” of armour.

To keep moving forward despite constant pressure, you'll also need tenacity. Tenacity comes into play when there's a goal that you or the team must strive achieve. When the team are working on delivering a critical objective they will put up with challenges and frustrations that otherwise would not be tolerated. Tenacity can get you and the team to do things you wouldn't otherwise think yourself capable of.

Enthusiasm will help you stay passionate and find pockets of creativity in spite of pressure. Enthusiasm gives you and the team energy to keep working and doing your best. It can be like a virus in that it is quickly catching, positively affecting those around you. Even in situations where pressure has almost killed your creativity, enthusiasm can kick it back into gear.

This is similar to “The Pressure Principle”, by Dr. Dave Alred who provides insights into performing under pressure, based on extensive experience as a performance coach. He talks about:-

The Three Cs: Confidence, Commitment, and Control as the essential building blocks to handling pressure effectively.

• Confidence: Built through practice, positive self-talk, and focusing on past successes.

• Commitment: Staying dedicated to goals and maintaining focus.

• Control: Focusing on factors within your control rather than external uncertainties.

Leaders Must Eliminate the Noise

High pressure situations create a deafening “noise” which is a serious distraction to decision making and importantly judgement.

In the end, it’s not the noise in your life that matters, but how you dance to the tune.”, Richard Paul Evans

The book “Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgement”, by Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R examines the variability in human judgement and its impact on decision-making processes. The book explores the concept of “noise,” defined as the unwanted variability in judgements that should ideally be identical but in chaos and under extreme pressure it can manifest in different ways.

Understanding Noise

- Definition: Noise is the variability in decisions made by different people or by the same person at different times, under similar circumstances or extreme pressure

- Types of Noise: The book identifies three types:

- Level Noise: Differences in average judgement levels between individuals or groups.

- Pattern Noise: Differences in judgement patterns due to inconsistent application of criteria.

- Occasion Noise: Variability in judgements due to temporary factors like mood or environment.

The Impact of Noise

- Decision-Making: Noise leads to inconsistent and unfair decisions in various fields, including law, medicine, hiring, and performance evaluations.

- Costs of Noise: Inconsistent judgements can have significant economic, social, and personal costs.

Examples of Noise

- Legal System: Sentencing decisions by judges vary widely, even for similar cases, highlighting significant level and occasion noise.

- Healthcare: Doctors often give different diagnoses or treatment recommendations for the same patient, leading to variability in medical care.

- Business: Hiring decisions, performance reviews, and strategic choices often suffer from noise, affecting organisational effectiveness.

Human Judgement and Bias

- Bias vs. Noise: While bias is a systematic deviation in one direction, noise is random scatter. Both affect the quality of decisions, but noise often goes unnoticed and unaddressed.

- Cognitive Psychology: The book delves into cognitive biases that exacerbate noise, such as overconfidence, anchoring, and availability heuristics.

Reducing Noise

- Decision Hygiene: The authors propose a series of practices to reduce noise in judgements:

- Structured Decision-Making: Using standardised procedures and checklists to ensure consistency.

- Guidelines and Algorithms: Implementing evidence-based guidelines and decision algorithms to minimise human judgement variability.

- Noise Audits: Conducting audits to identify and measure noise within an organisation and develop strategies to reduce it.

Algorithms vs. Human Judgement

- Algorithmic Decision-Making: The book advocates for greater use of algorithms, which are less prone to noise than human judgement. Algorithms provide consistency, although they must be carefully designed to avoid biases.

- Human Oversight: While algorithms can reduce noise, human oversight is necessary to handle exceptions and ensure ethical considerations.

Implementing Change

- Cultural Shift: Reducing noise requires a cultural shift within organisations to prioritise consistency and recognise the impact of noise.

- Training and Education: Training programs to educate decision-makers about noise and how to mitigate it are essential for long-term change.

The Role of Training and Preparation

“Under pressure, we do not rise to the occasion, we revert to our level of training.”

Preparation and training are fundamental to improving decision-making under pressure. Scenario-based training, simulations, and role-playing exercises can replicate the stress and urgency of real-life crises, allowing individuals to practice and refine their decision-making skills in a controlled environment. For instance, pilots undergo rigorous simulator training to prepare for emergency situations they might encounter mid-flight. Such training helps build muscle memory and cognitive resilience, enabling more effective responses during actual crises.

In the healthcare sector, disaster drills and emergency response simulations are common. These exercises help medical staff practice their roles in a crisis, ensuring that they can work together effectively under pressure. Similarly, law enforcement and emergency responders regularly engage in mock disaster scenarios to hone their skills and improve coordination.

Business leaders can benefit from crisis management training, which often includes simulations of market crashes, product failures, or public relations disasters. These exercises help executives develop the ability to make quick, informed decisions while managing the emotional and psychological impacts of high-pressure situations.

Collective Decision-Making in Crises

Effective decision-making under pressure often requires teamwork and collaboration. Diverse perspectives can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the situation and generate a wider range of potential solutions. However, coordinating a team under stress presents its own challenges. Clear communication, defined roles, and strong leadership are essential.

Leaders must be able to delegate tasks effectively, ensuring that team members know their responsibilities and have the resources they need. Communication should be concise and direct, avoiding ambiguity that could lead to misunderstandings. Leaders must also be capable of inspiring confidence and maintaining morale, even when the situation appears dire.

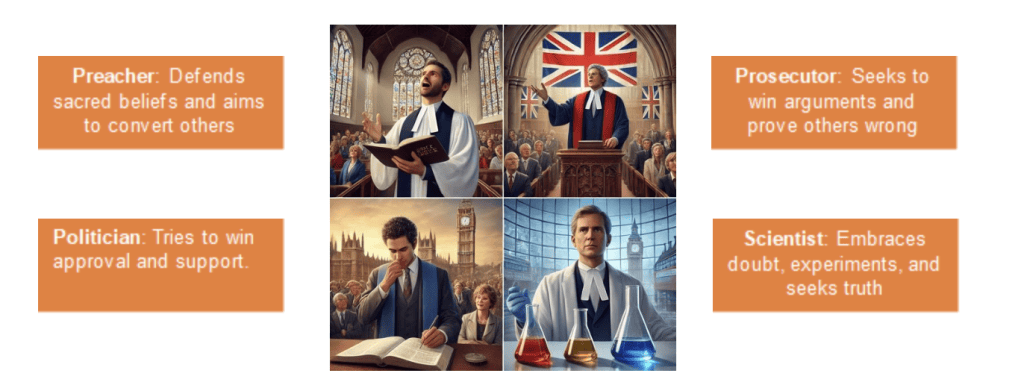

In the book, ‘Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know’, by Adam Grant is a compelling exploration of the importance of rethinking and unlearning particularly in a pressurised crisis situation, rather than clinging to outdated beliefs and assumptions which can damage judgement.

Grant argues that cognitive flexibility and the ability to rethink are crucial for personal and professional growth. He emphasises the importance of being open to new information and perspectives, and not being overly attached to one’s current beliefs.

It introduces the concept of the rethinking cycle, which involves:

- Doubt: Questioning one’s own knowledge and beliefs.

- Curiosity: Seeking out new information and experiences.

- Discovery: Gaining new insights and perspectives.

- Humility: Acknowledging what one doesn’t know and being willing to change.

The book also contrasts different mindsets that affect our ability to rethink:

He advocates adopting the scientist mindset to continually question, test, and revise beliefs based on evidence.

Learning from Experience

“Courage is not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it”, Nelson Mandela.

The book, ‘Deep Survival: Who Lives, Who Dies, and Why’, by Laurence Gonzales delves into the psychology and biology of survival in extreme conditions. Gonzales combines real-life survival stories with scientific analysis to uncover the traits and behaviours that determine who survives life-threatening situations and who doesn’t.

Gonzales describes various survival scenarios, from mountaineering accidents to shipwrecks and wilderness emergencies. These stories highlight the unpredictability and severity of life-threatening situations. It examines individuals who survived against the odds, identifying common traits and behaviours that contributed to their survival.

Survivors often display heightened situational awareness and the ability to perceive threats accurately. They acknowledge the reality of the situation and accepting it without denial is critical for effective problem-solving always maintaining hope and a positive outlook, even in dire circumstances, can significantly impact survival chances.

Behavioural traits of these survivors include:

- The ability to adapt to changing circumstances and remain flexible in approach is vital.

- Resourcefulness using available resources creatively and efficiently can make the difference between life and death.

- Tenacity and perseverance demonstrating a strong will to live and the persistence to keep trying, even when the situation seems hopeless.

Survival strategies varied but common themes appeared:

- Being prepared with the right skills and knowledge increases survival chances. Regular training helps ingrain these skills so they can be accessed under stress.

- Managing emotions and staying focused on immediate tasks helps maintain clarity and prevent panic.

- Making clear, rational decisions based on available information and prioritising actions is crucial.

Gonzales acknowledges the role of luck and randomness in survival situations. Sometimes, despite best efforts, uncontrollable external factors can determine the outcome.

Survivors often have a keen understanding of risks and probability taking calculated actions to mitigate them. The law of probability helps us quantify how likely events are to occur. By understanding and applying basic principles such as the probability formula, adding and multiplying probabilities, the complement rule, and conditional probability, we can make more informed decisions in business and everyday life.

Examples of some of the survivors used in the book:-

Steven Callahan: Lost at Sea

Circumstances:

Steven Callahan was sailing alone across the Atlantic when his boat, the Napoleon Solo, struck an unknown object and began to sink. He managed to deploy his life raft, taking with him some supplies, including a spear gun, a solar still for purifying water, and a survival manual.

Survival Actions:

- Resourcefulness: Callahan used the solar still to produce fresh water and the spear gun to catch fish.

- Adaptability: He continuously adapted to the harsh conditions by repairing his raft, managing his limited supplies, and making use of the marine life around him.

- Mental Resilience: Callahan kept a daily log, which helped him maintain a routine and preserve his mental health.

- Positive Outlook: He visualised positive outcomes and set small, achievable goals to stay motivated.

Outcome:

- Callahan survived for 76 days at sea before being rescued, demonstrating extraordinary endurance and ingenuity.

Beck Weathers: Mount Everest Disaster

Circumstances:

Beck Weathers was part of a 1996 expedition on Mount Everest that encountered a severe storm. Weathers suffered from severe frostbite and was left for dead twice as he was unable to move or communicate effectively.

Survival Actions:

- Sheer Willpower: Despite his condition, Weathers regained consciousness and managed to stagger back to camp with minimal vision and severe injuries.

- Mental Resilience: His determination to return to his family motivated him to push beyond the limits of his physical endurance.

- Self-Reliance: Weathers used his mountaineering knowledge to navigate back to camp despite debilitating conditions.

Outcome:

- Beck Weathers survived against all odds and underwent numerous surgeries for his injuries. His story is a testament to the power of human will and mental strength in survival.

Post-crisis reflection is crucial for improving future decision-making. After the immediate danger has passed, organisations should conduct thorough reviews to understand what worked well and what didn’t. This process, often called a “post-mortem” or “after-action review,” helps identify strengths and weaknesses in the response and develop strategies for improvement.

Analysing decisions and actions taken during a crisis can reveal valuable insights. For example, did the decision-making process effectively incorporate all available information? Were there communication breakdowns that hindered the response? Did the team demonstrate resilience and adaptability? Learning from these reviews can enhance training programs, refine procedures, and strengthen overall preparedness.

Final Thoughts and Guidance

So how can Uspire help leaders in these situations:

Here’s our diagram that outlines the eight stages for dealing with decision-making under extreme pressure:

Decision Making Under Extreme Pressure

‘The greatest weapon against stress and pressure is our ability to choose one thought over another’, William James

- Recognise the Situation: Identify that a critical decision is needed.

Be aware of the environment and acknowledge the urgency and gravity of the situation.

- Stay Calm and Focused: Manage emotions and maintain clarity.

Use techniques such as controlled breathing and mindfulness to stay composed.

- Gather Information: Collect relevant data and inputs.

Obtain as much accurate information as possible from available sources.

- Assess the Options: Consider possible courses of action.

Brainstorm and list potential solutions or actions.

- Evaluate Risks and Benefits: Weigh the potential outcomes and consequences.

Analyse the pros and cons of each option, considering short-term and long-term effects.

- Make the Decision: Choose the best option based on the analysis.

Decide on the course of action that offers the most benefits with acceptable risks.

- Act Decisively: Implement the chosen action quickly and effectively.

Execute the decision with confidence and efficiency, ensuring clear communication.

- Review and Learn: Reflect on the decision and outcomes to improve future responses.

After the action, assess what worked, what didn’t, and how processes can be improved for future situations.

Managing the emotional impact.

“Calm mind brings inner strength and self-confidence, so that’s very important for good health”, Dalai Lama.

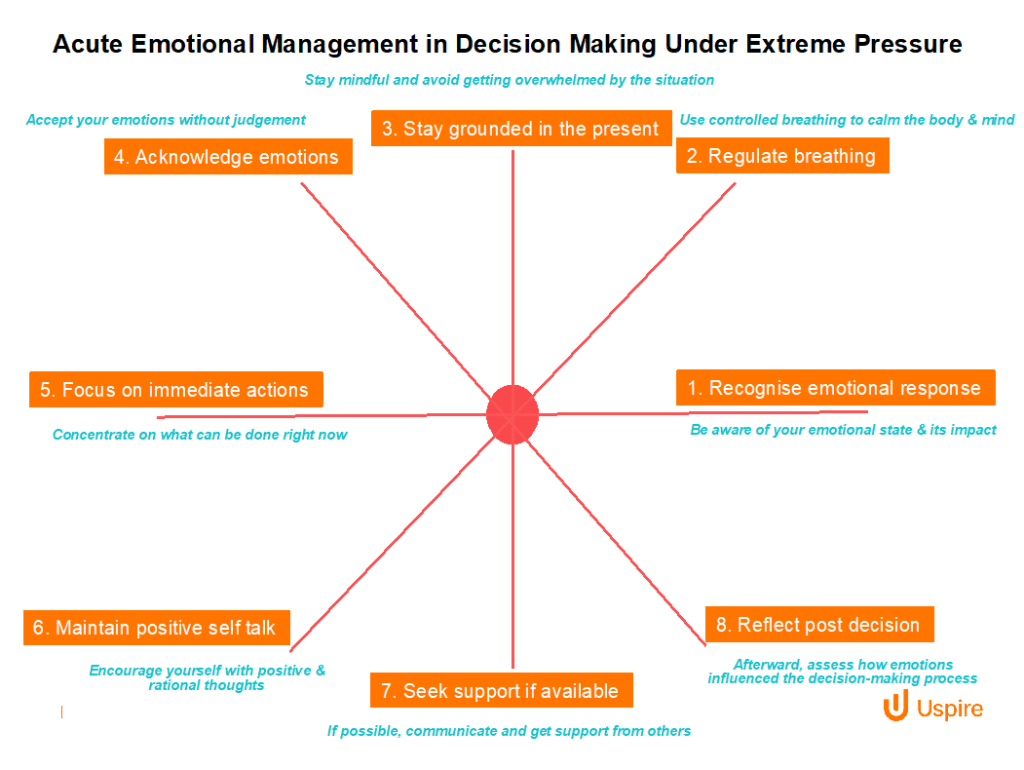

Here is the Uspire circular diagram model that assesses the acute emotional side of making decisions under extreme pressure:

Acute Emotional Management in Decision Making Under Extreme Pressure

- Recognise Emotional Response: Be aware of your emotional state and its impact. Understand how your emotions are influencing your thoughts and actions.

- Regulate Breathing: Use controlled breathing to calm the body and mind. Practice deep, slow breaths to reduce stress and regain focus.

- Stay Grounded in the Present: Stay mindful and avoid getting overwhelmed by the situation. Focus on the here and now, using techniques like grounding exercises.

- Acknowledge Emotions: Accept your emotions without judgement. Recognise what you are feeling without trying to suppress or ignore it.

- Focus on Immediate Actions: Concentrate on what can be done right now. Break down the situation into manageable tasks and prioritise immediate actions.

- Maintain Positive Self-Talk: Encourage yourself with positive and rational thoughts. Replace negative thoughts with constructive affirmations.

- Seek Support if Available: If possible, communicate and get support from others. Reach out to colleagues or friends for emotional or practical support.

- Reflect Post-Decision: Afterward, assess how emotions influenced the decision-making process. Review the decision and its outcomes to understand the role emotions played and learn for the future.

This model helps individuals manage the acute emotional aspects of high-pressure decision-making, ensuring that emotions are acknowledged and regulated to maintain clarity and effectiveness.

Making decisions under extreme pressure or in a crisis is a vital skill for the finest leaders across various domains. It requires a combination of physiological management, psychological resilience, rigorous training, and practical experience. By understanding the impact of stress on the brain and employing strategies to mitigate its effects, leaders can enhance their ability to make sound decisions when it matters most. This not only improves outcomes in critical situations but also builds a foundation for more effective leadership and management in everyday life. Whether in healthcare, the military, business, or any other field, the ability to navigate high-pressure environments with clarity and composure is indispensable. Through continuous learning and adaptation, individuals and organisations can strengthen their crisis response capabilities and improve their resilience against future challenges.

“The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

Martin Luther King Jr.