It has been quite a while since the Uspire Network issued an economic update and a lot of crucial questions are being asked by leaders.

In simple terms the economy includes all activities in the country concerned with the manufacturing, distribution and the use of goods and service-based enterprises. The economic climate has a big impact on businesses.

The level of consumer spending affects prices, investment decisions and the number of workers that businesses employ.

With our USPIRE overview the economic climate affects businesses in broadly ten ways:

- Available labour pool

- Changing levels of consumer income

- Inflation

- Interest rates

- Tax rates

- Exchange rates

- Recession/GDP growth

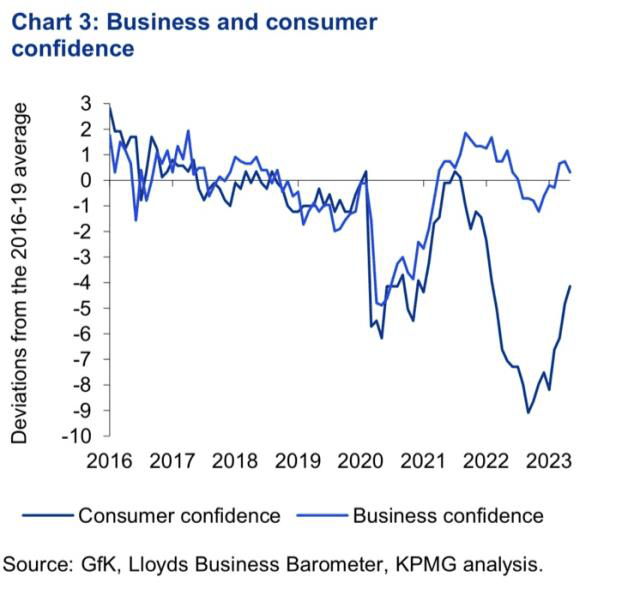

- Consumer confidence

- Supply and demand

- Changes in import legislation

These are generally managed by two strategies.

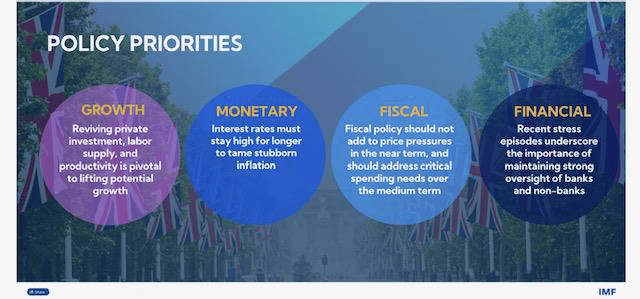

Fiscal policy is the government policy that impacts taxation and government spending. It can either be expansionary for growth and development with the aim of increasing economic activity by expanding Government spending and/or decreasing taxation.

Fiscal policy can also be contractionary, which aims to reduce economic activity by driving up taxation and/or reducing the amount of government spending.

Monetary policy involves changing the supply of money in an economy. This involves adjusting interest rates also manipulating exchange rates and controlling the money supply. The objective of monetary policy is to keep inflation rates stable and at a level to promote economic growth. In the UK, monetary policy and setting interest rates are the responsibility of The Bank of England.

What these do not factor in well is the behavioural changes in society no algorithm is available to accurately predict human behaviour. A great example is the unexpected way that the UK recovered from Covid, how consumers reacted post lockdown, all this happened much faster than any forecast.

18 months ago, we talked about the four horsemen of the business apocalypse.

These were: -

Labour shortages

High Debt

High Inflation/supply chain disruption

Consumer Uncertainty/Confidence

While the shape of these factors has changed, they are still very much playing havoc with our decision making.

In this blog we look at these factors by drawing relevant expert opinion and adding some of our own interpretation.

Let’s turn to the Bank of England’s own perspective on the UK and its economic challenges.

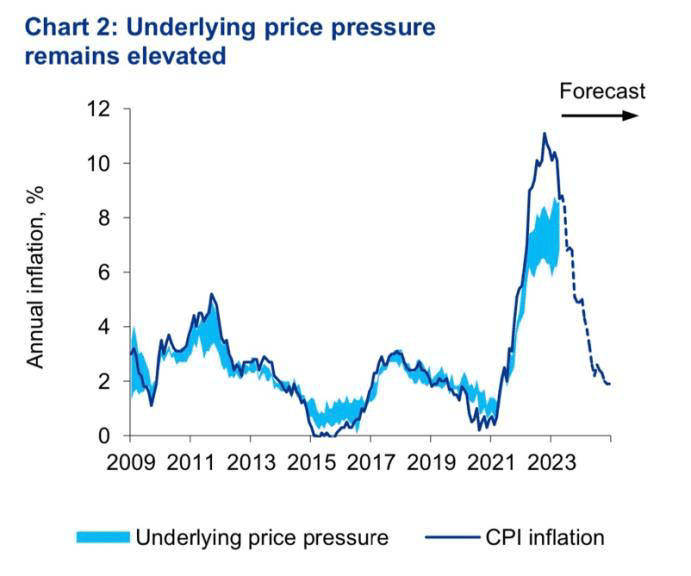

Why is inflation high?

High inflation has been caused by a series of big shocks to our economy.

The first shock was the Covid pandemic. While people had to stay at home, they started to buy more goods rather than services. But the people selling these goods have had problems getting enough of them to sell to customers. That led to higher prices, particularly for goods imported from abroad.

The second shock was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which led to large increases in the price of gas. It also pushed up the price of food. Poor harvests in other countries made the situation worse. Food prices in June were 17% higher than a year ago.

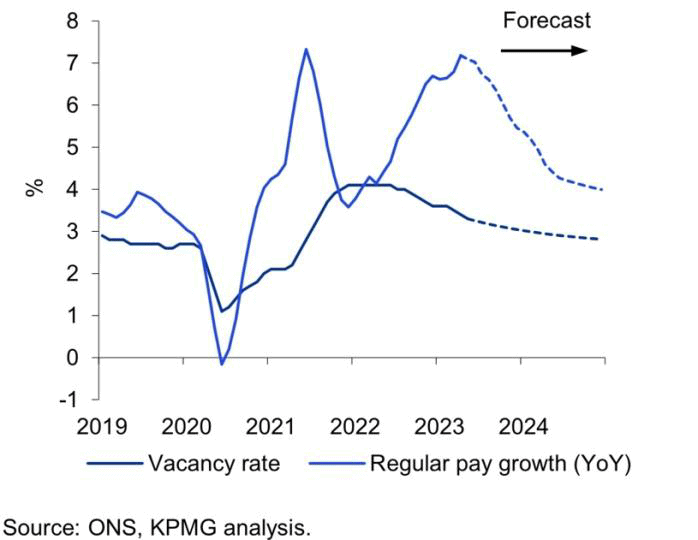

The third shock was a big fall in the number of people available to work. That was linked to the Covid pandemic. It’s meant that employers have had to offer higher wages to attract job applicants. Many businesses have had to increase their prices to cover those costs. That includes firms in the services sector, where wages are the largest part of business costs.

How does raising interest rates lower inflation?

People have asked the Bank of England why putting up UK interest rates will help. Some say it won’t tackle the causes of the inflation and it will only make the squeeze on household finances even worse.

Higher interest rates work by making it more expensive for people to borrow money to buy things. Higher interest rates also encourage people who can save to save rather than spend. Together, these things mean there will be less spending in the economy overall.

When people spend less on goods and services overall, the prices of those things tend to rise more slowly. Slower price rises mean a lower rate of inflation.

We know higher interest rates are hard for many people. But we must take this action to make sure inflation comes down and stays down.

Having high inflation for a long time would cause even greater hardship, especially for the least well-off and those in unsecure employment.

The action we take to keep inflation low and stable is called monetary policy.

Our Uspire Network opinion supported by narrative from the Henley Business School is as follows:-

When economic activity is high, i.e., companies can sell products and services in the desirable quantities without systematically decreasing their prices, companies are eager to expand production in order to profit from the customer willingness to spend. This "eagerness" leads to companies competing with other companies for the same resources (raw materials, talent, professional services etc).

Many companies are eager to "beat" competition for resources by paying higher prices, such as paying higher salaries or more for the same quantity of raw materials. That creates a domino effect in rising prices as, for instance, employees with higher salaries will spend more in their private life, competing, in turn, with other consumers for products or services that cannot increase in quantity or availability in the short run. Their consumption, then, leads to companies seeking further growth to capture the buoyant

demand for their offering. This flywheel effect in increasing prices is what maintains high inflation or, to reflect the widespread effect in the economy, a "high inflationary environment".

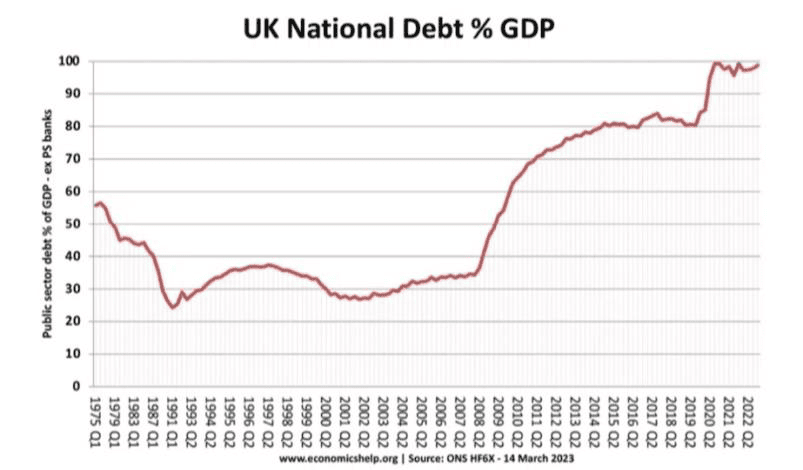

This opinion of supply and demand factors was originally anchored in the days of people spending too much money on credit cards or borrowing money and spending excessively on luxury goods rather than essentials. Inflation during the past eighteen months is driven by different factors, Covid, Brexit and the war in Ukraine. During Covid there was a massive expansion in government debt, all of which was financed by the central bank. So Covid drove both expansionary fiscal and monetary policy. The expansion was $17 trillion globally, and $900 billion in the UK. The inevitable result is a surge in average price levels of everything i.e., land, buildings, labour, materials.

Brexit due to a focus on immigration reduced labour supply in the UK and complicated the import of goods from the EU, and of course this was compounded by the war in Ukraine. However, are we really spending to excess on fuel to heat homes or putting food on plates? The impact in the hospitality sector and retail would not suggest we have been spending to excess apart from the brief six-month period of demob enthusiasm and excitement of being released from lockdown.

The theory is that raising interest rates makes borrowing more expensive, encourages saving, discourages spending, reduces demand and therefore helps slow down price rises. However, we would argue that the UK still faces the prospect of dipping into recession now because of these unusual sources of inflation and it is not the time to be imposing measures that cool the economy down. The Bank of England have used interest rates as a blunt instrument a sledgehammer to crack a nut and not factored in changes in human behaviour driven by three unique events.

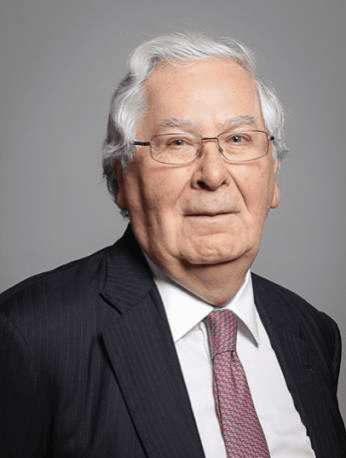

Mervyn King a man to respect had this to say recently about continually raising interests.

That the Bank of England could plunge the UK into a recession by raising rates too far, he said the signals from the credit markets in 2021 that indicated inflation was about to rocket were now showing that price growth was about to drop sharply.

King said officials on the monetary policy committee could tighten monetary policy too far if they pushed for further rate increases, triggering a recession.

He said the central bank had ignored signals from money supply data, which pointed to higher inflation coming out of the pandemic.

The Bank has defended its position, saying it delayed acting to calm inflation, believing the economy would go through a period of weak growth and higher unemployment after the furlough scheme ended which did not happen.

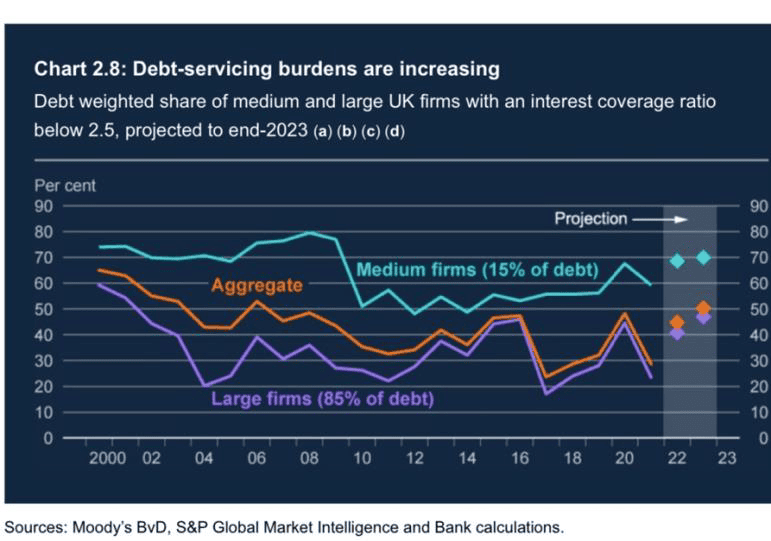

The former governor’s comments add to concerns about the Bank’s most aggressive series of rate rises in three decades and the impact it is having on the economy. Mortgage rates have risen sharply, and some economists have predicted unemployment could increase next year as corporate bankruptcies rise due to debt burdens and job vacancies fall.

Money supply economists claim to have predicted the steep rise in inflation before it jumped to more than 10% in 2022. They have warned that a contraction in the supply of money to consumers and businesses after 13 consecutive increases in interest rates will mean inflation reverses quickly without the need for further action.

King said: “The risk is that having ignored money when inflation was rising, they’re now ignoring money when inflation is actually about to fall. What we could see, therefore, is a mistake in both directions over a period of three or four years.

“If they carry on for the next six months or so tightening monetary policy, it could well be that they generate both a recession as well as a sharp fall in inflation.”

King’s criticism follows similar comments by the Bank of England’s former chief economist Andy Haldane, who argued for a sharp increase in borrowing costs in 2021 before commenting in April that the central bank had gone far enough.

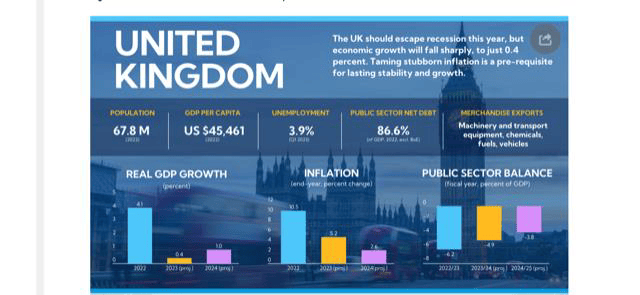

The International Monetary Fund currently have this view of the UK: -

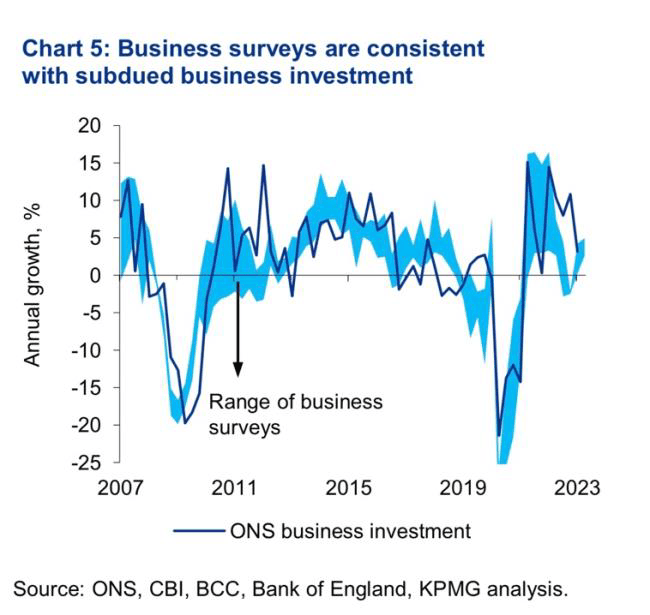

Prior to the 2008 global financial crisis, the UK had been a strong performer among the Group of Seven countries. But this momentum was lost in the middle of the last decade. By 2022, real business investment was still slightly lower than in 2016, in contrast to the 14 percent increase among other G7 economies. Labour supply, which has just reached its pre-pandemic level, has also been weaker than peers. As in other advanced economies, productivity growth has been sluggish, reflecting a slower pace of innovation and technological diffusion.

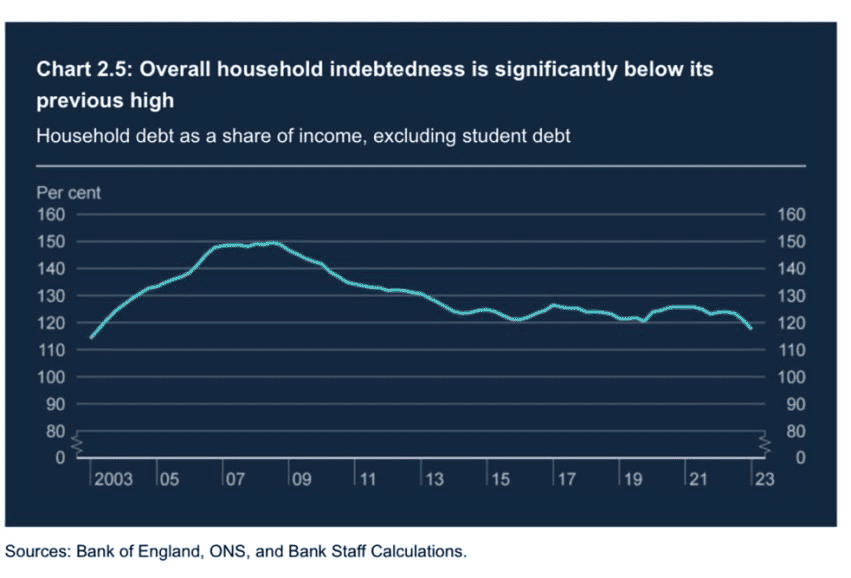

Here are the key charts: -

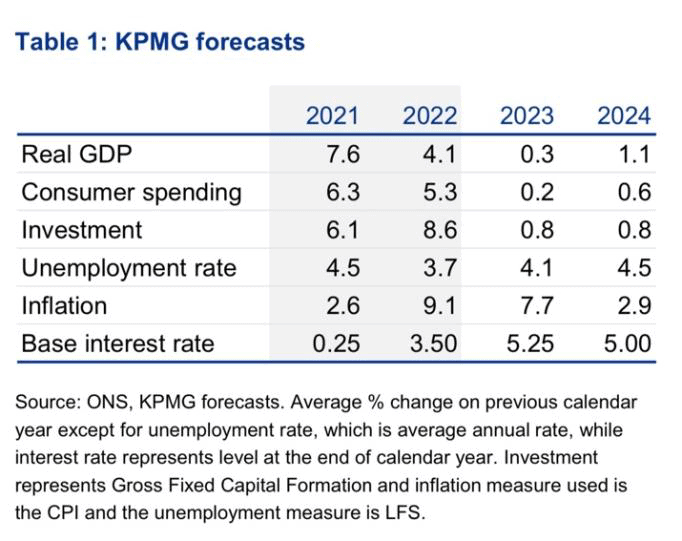

What do the numbers look like?

- The impact of rising interest rates which have a delayed effect on economic growth means the UK economy is only expected to grow 0.8% in 2024, down from April’s 1.9% forecast.

- Inflation is still expected to fall at pace in the final quarter of 2023, and the UK remains on course to avoid recession.

- Overall, inflation is expected to average 7.6% this year (up from April’s 6.2% forecast), before falling to 3.4% in 2024 (up from 2.5%) and 1.7% in 2025. The Bank of England isn’t expected to reach its 2% inflation target until late 2024.

- A strong start to 2023 for business investment means 1.4% growth is now expected this year, up from the 0.3% contraction forecast in April. But higher interest rates will limit businesses’ appetite to spend in 2024.

- Food inflation is expected to fall to 6% by the end of the year, from just over 17% in June.

- Average earnings are expected to grow 5.8% this year (up from 4.2% in April), 3.1% in 2024 and 2.6% in 2025.

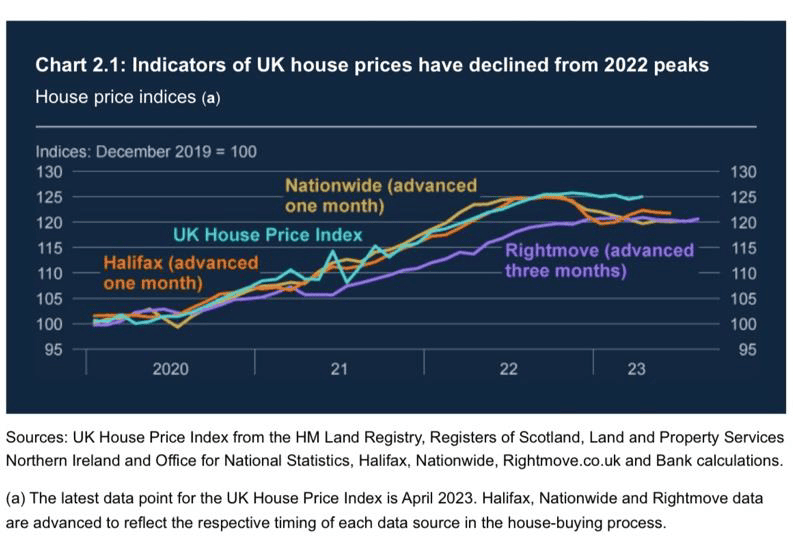

- With higher interest rates making mortgages more expensive, house prices are expected to stagnate in 2023, before falling by 4% in 2024.

- Although 1.6 million home owners will have to renew over the next 12 months it will be a challenge as they shift from 2% to 6-8%.

- The output gap is an estimate of how much spare capacity the economy has. It’s estimated at 0.1% of GDP currently. This means overall the UK has virtually no spare capacity this must change.

- Currently the UK government is spending £45 billion more than its income from tax. The USA is spending $1.5 trillion more.

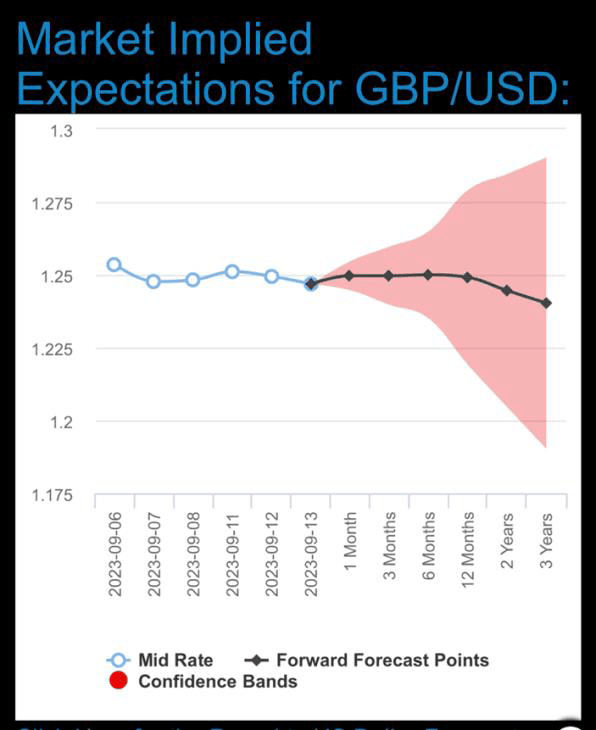

- Dollar exchange rate currently at $1.25 but could move towards $1.33-35 over the next three months. This would then strongly suggest that the market think the Bank will raise base rate beyond 5.25%.

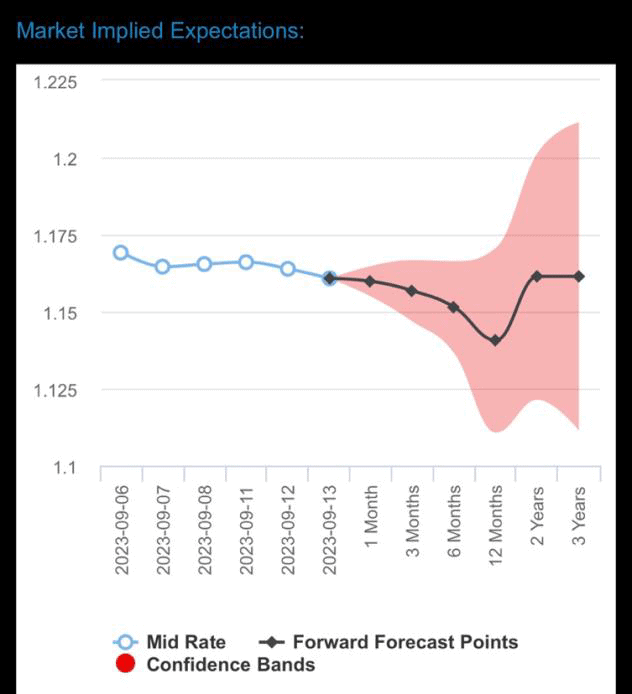

- The Euro rate is 1.16 and we doubt it will go beyond 1.18 in 2023.

UK Equities

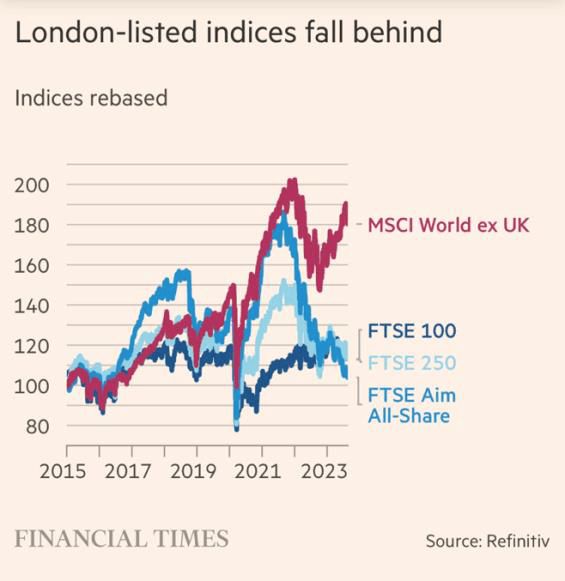

What is the outlook for UK equities are they undervalued?

Here is what the Financial Times are saying, and this backed up by several financial institutions.

A Morgan Stanley analysis published last month found that core UK plc assets, equities and corporate bonds “are arguably the cheapest asset classes in the world”. That position is particularly remarkable given the FTSE 100 was the best-performing major global index of 2022 (by staying basically flat).

UK equities’ plunge into record discount territory versus global stocks can be traced back to the referendum in 2016. On one crude indicator, price/earnings, FTSE 350 stocks were virtually equally valued to global shares on the eve of the referendum, with both at 18.6 according to Bloomberg data. Now they’re about half the price: as of last Thursday, the FTSE 350 had a price/earnings ratio of 10, while MSCI’s World Index stood at 19.8.

So, what conclusion can we draw from these figures and forecasts? We have reviewed the outlook from one of our Uspire Network speakers the economist Roger Martin-Fagg and many of his opinions are consistent with ours.

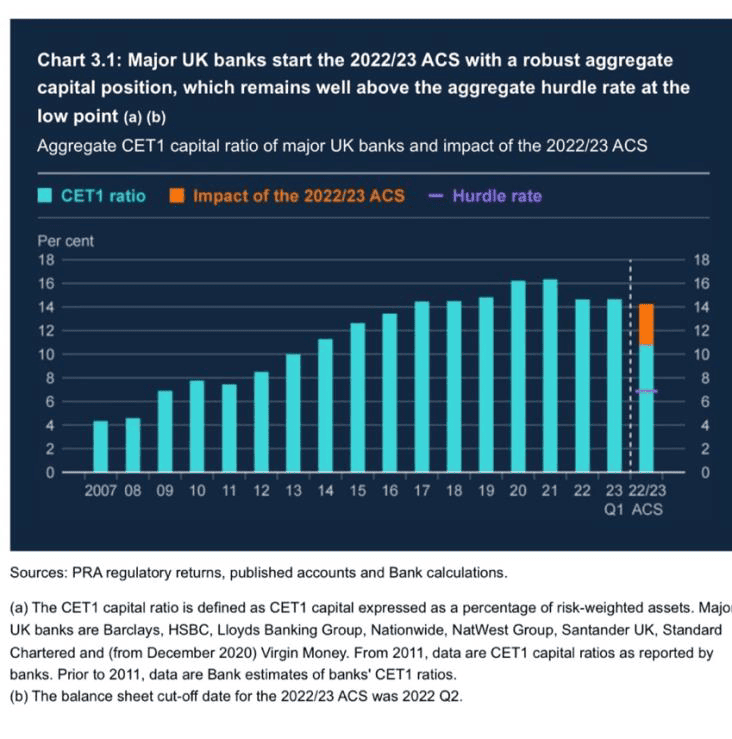

We will just avoid a recession and the good news is that the banks remain well capitalised and can help support the governments mountain of future toxic Bounce Back and CBIL debt from zombie companies.

Interest rates will not move significantly higher with a maximum of 0.25% in the next 6 months.

Inflation will return to a level of around 3.5% by the start of 2025 when interest rates will fall to around 3%.

The predictions for GDP growth are around 1-1.3%. We agree with Roger that any growth above 1.1% will require significant investment because of the inevitable poor UK labour availability over the next ten years must be driven by AI.

House prices will fall but not collapse as will commercial property values.

The housing market will benefit from the support of family members, as Roger puts it ‘the Bank of Mum and Dad’ and there are still £125 billion of excess deposits in ‘the Bank of Mum and Dad’.

Most importantly 80% of mortgages are joint. Which is technically two incomes, both of which are likely to be going up 5-10% depending on job and location.

8.8 million are earning around £50,000pa in 2022. 9 million households have a mortgage which is just 30% of households.

During 2022 the monthly average mortgage payment was £2000 per month, and it is anticipated by the end of this year it will be around £2400 a month. The average mortgage is between £180-200k. According to the BofE statistics in 2023 only 40% of house purchase was actually debt, the rest cash. Pre-Covid the figure was closer to 50% which is a significant difference.

Labour inflation will continue at around 5% because of lack of availability and lower immigration/freedom of movement. It will not drop to 2.5-3% that others are predicting.

We may not be totally happy with the governments or Bank of England’s approach to resolving inflation, but the conservatives are attempting to hold onto votes so radical changes to stimulate the economy are unlikely. As the chief economist at the Henley centre suggested if you had just won an election, you would significantly increase taxes to reduce government debt then look to stimulate the economy via investment.

Alternatively, the government could try an alternative economic strategy that industry and retail might prefer.

Supply-side economics is a theory that postulates economic growth can be most effectively fostered by lowering taxes and decreasing regulation thus allowing free trade. According to supply-side economics, consumers will benefit from greater supplies of goods and services at lower prices, and employment will increase. Supply-side fiscal policies are designed to increase aggregate supply as opposed to aggregate demand thereby expanding output and employment while lowering prices. Such policies are of several general varieties: -

- Investments in human capital, such as education, healthcare, and encouraging the transfer of technologies and business processes, to improve productivity (output per worker). Encouraging globalised free trade via containerisation is a major recent example.

- Tax reduction, to provide incentives to work, invest and take risks. Lowering income tax rates and eliminating or lowering tariffs are examples of such policies.

- Investments in new capital equipment and research and development (R&D), to further improve productivity. Allowing businesses to depreciate capital equipment more rapidly (e.g., over one year as opposed to 10) gives them an immediate financial incentive to invest in such equipment.

- Reduction in government regulations, to encourage business formation and expansion.

However, this requires careful management and a structured communication plan with detailed monetary forecasts. Support from the Bank of England and the stock markets with a strategy agreed to underpin the pound over the short term due to the initial monetary shock of a short-term deficit and increase in borrowing.

Unfortunately, they never managed the last part correctly and created a game called surprise without a supporting financial forecast!!!!!!

Final summary

The next 18 months is very difficult to forecast accurately. Primarily because human behaviour is volatile, unpredictable and strongly influenced by what we read.

The media are very downbeat and swing with the political rhetoric and this needs to change and requires confident positive leadership.

It’s also worth remembering that the markets respond steadily to good news but over react and panic with bad news. This is why after Brexit, Trussonomics and UK inflation our equities are still undervalued.

For leaders the most important advice is don’t over leverage with current interest rates and continue to review your cost base.

However, do spend wisely and ensure that your future investment strategy is clearly targeted at reducing labour costs. The cost of people will only increase and the demand for production workers and talent must rise.

Lead with optimism and bang the productivity drum, look forward not backwards, people need to see you bounce with enthusiasm.

Sources of Information

• Ernst and Young

• IMF

• KPMG

• Henley Business School (Dr Nikolaus Antypas)

• CBI

• Financial Times

• Bank of England

• Roger Martin-Fagg

• Coutts & Co